A few months ago I received a preview copy of American Experience?s Death and the Civil War, which will air on PBS this week.? This weekend I finally had a chance to watch it through, which seems appropriate given that we are commemorating the 150th anniversary of the battle of Antietam.? I am not going to offer a comprehensive overview of the show.? For the most part I enjoyed it even if the Ken/Ric Burns format has become predictable.? The program is based largely on Drew G. Faust?s recent book, This Republic of Suffering: Death and the American Civil War

A few months ago I received a preview copy of American Experience?s Death and the Civil War, which will air on PBS this week.? This weekend I finally had a chance to watch it through, which seems appropriate given that we are commemorating the 150th anniversary of the battle of Antietam.? I am not going to offer a comprehensive overview of the show.? For the most part I enjoyed it even if the Ken/Ric Burns format has become predictable.? The program is based largely on Drew G. Faust?s recent book, This Republic of Suffering: Death and the American Civil War, which I highly recommend.? For an overview of the program check out reviews by Megan Kate Nelson at The Civil War Monitor and Michael Lynch at Past in Present.

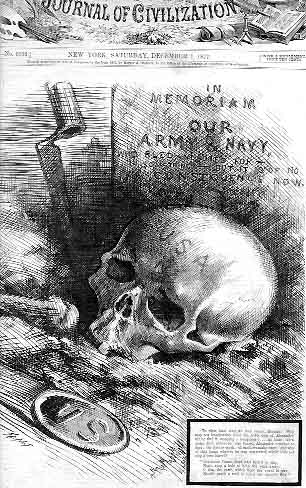

The one aspect of the program that I found disappointing was the continued difficulty to acknowledge the ways in which Americans (mainly northerners) came to terms with their dead as part of the sacred work of preserving the Union.? The coverage of how the Civil War challenged the Victorian era idea of a ?good death? is captured beautifully through images, words, and music, but just as important to Victorian America was the striving toward connecting that death and suffering to the sacred cause of Union.? American Experience bombards the viewer with the emotional and psychological toll of death, but without much in terms of redemption.? No doubt, I?ve been influenced by having recently read Frances M. Clarke?s War Stories: Suffering and Sacrifice in the Civil War North.? No other book that I know of more effectively explains how northern stories of suffering and death produced by soldiers on the front as well as on the home front galvanized sectional pride and morale throughout the war.

One of the most interesting chapters in the book is a case study of the death and memory of Nathaniel Bowditch, a second lieutenant from Massachusetts, who was killed in 1863.? Nathaniel?s letters home reflect his commitment to the virtues of bravery and selflessness as well as the understanding that his actions and possible death would help to shape a crucial moment in world history.? His letters home, like those of others, would help family members to deal with the pain of loss by acknowledging that it was a meaningful death.? Nathaniel?s death is featured prominently in Death and the Civil War, specifically his father Henry?s difficulty in coming to terms with the loss of his son.? The viewer feels the emotion of Henry?s loss, but not his striving to ensure that it was a heroic death.? All we learn is that Henry eventually authored a manual that promoted the use of ambulances on the battlefield.? What we don?t learn is that almost immediately following his death, Henry sought out Nathaniel?s comrades and superior officers for any information that might assuage his family?s concerns about the way his son died on the battlefield.

Even the beautiful scrapbooks that Henry lovingly created with his son?s letters as well as those sent to him from family members and other mementos are only briefly mentioned at the very end of the program.

The memorials that they created reveal a lurking fear that battlefield deaths might come to be seen as meaningless slaughter, but they also show why such interpretations failed to gain currency at this time.? In this war, heroism held meaning insofar as a soldier displayed an admirable character that reflected well on his family and community.? To become a heroic martyr, officers had to perform conscientiously, suffer physical or emotional torments without undue complaint, exhibit moral conviction and self-control at the point of death, and embody all of those other character traits that represented with worthiness of their family and class backgrounds?. Henry Bowditch purposefully included the family?s letters to show just how much homefront support and prodding went into creating a heroic martyr.? He was proud of that fact.? He wanted to show that they held Nathaniel to a high standard of uncomplaining selflessness while expecting nothing less of themselves.? As the Bowditch parents worked so hard to prove at the moment of their greatest loss, it was both the burden and expression of a truly virtuous elite to model suffering?s inspirational potential. (p. 48)

Perhaps we are far too removed from the Victorian world to truly appreciate what seem to be overly romanticized and sappy acts of memorialization.? The other problem is that we are much too quick to allow Lincoln?s Gettysburg Address to bring meaning to it all.? It?s as if Americans were just sitting around waiting for their president to utter those stirring lines and bring some level of comfort and reassurance to their households.? I am not suggesting that it didn?t, but family?s like the Bowditch?s were working to ensure that their dead did not die in vain from the beginning.? The other issue is that we still fall into the trap of seeing the war as void of meaning until emancipation comes on the scene.

Both of these themes come through loud and clear in Death and the Civil War and to that extent limit our understanding of how thousands of families struggled to come to terms with death.

Source: http://cwmemory.com/2012/09/16/death-and-dying-without-meaning/

tax day freebies madison bumgarner wnba draft tax day april 17 boston marathon tu pac hologram

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.